For a moment, imagine that you are one of the reserve’s willow warblers, a tiny grey-green bird, hunting spiders among the white willow trees and alders down by the Lambrok tributary stream.

The summer is over, it’s well into autumn and you are running late. Your two broods of healthy nestlings are fledged and gone, the moult is over and your new plumage is in perfect flying condition, you have gorged on a late hatch of water-fly and it’s time to head south.

Willow warbler (Phylloscopus Trochilus) and an old white willow by the Lambrok tributary

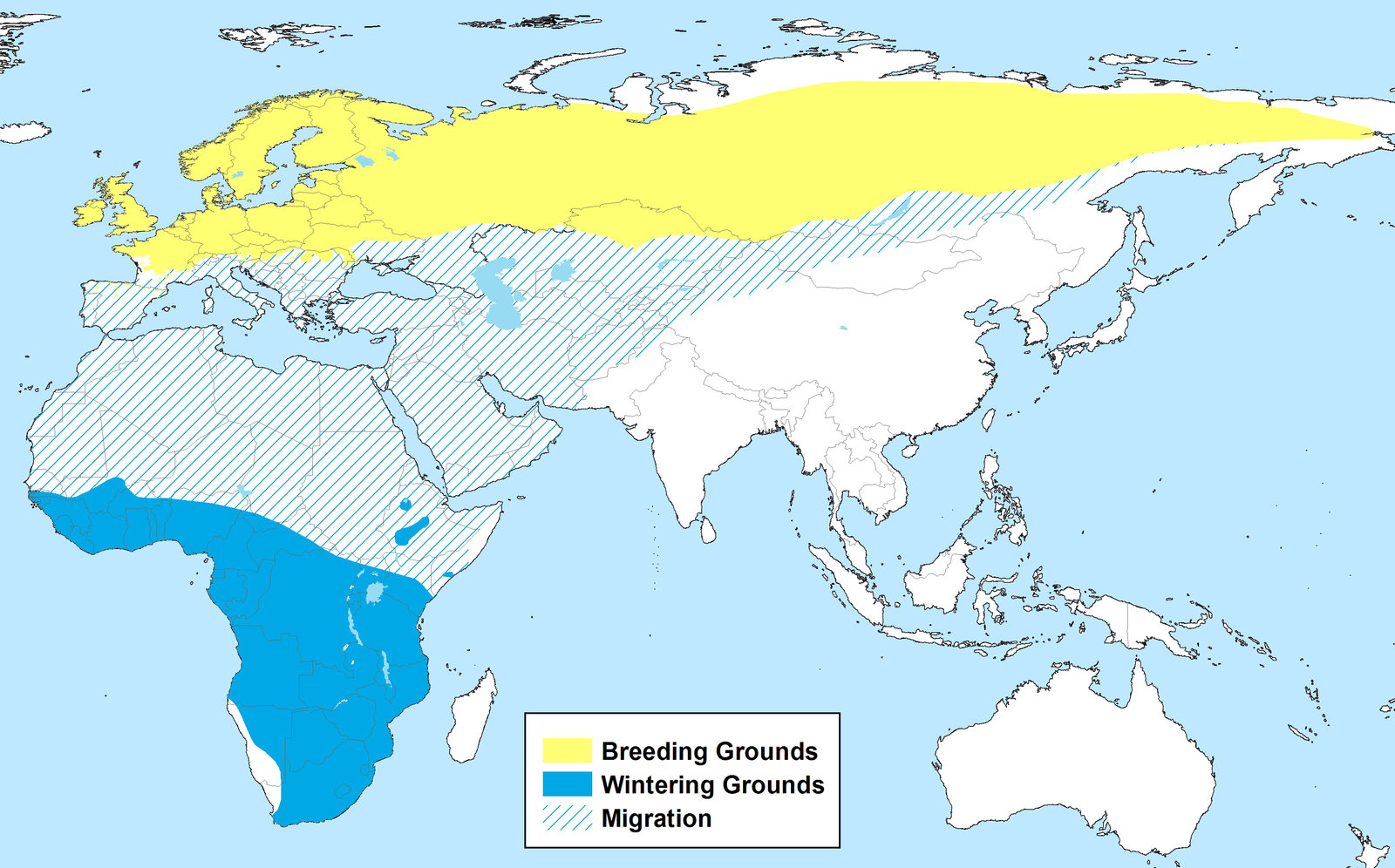

You weigh a smidgeon less than a couple of A4 sheets of paper and the journey you are contemplating is somewhere between six and twelve thousand miles, across the English Channel, through mainland Europe to the Pyrenees and Spain, over the Mediterranean at Gibraltar and then, the most dangerous obstacle of all, the Sahara Desert – and on into sub-Saharan Africa.

When you leave the reserve, how will you know where to go?

The routes south and one of the reserve’s willow warblers photographed by DKG

Navigation

The timing and the direction of the reserve’s willow warblers’ migratory flight is a matter of genetics. Each bird inherits its internal map and timetable from its parents. Other populations will have different maps and schedules: willow warblers from Scotland, for instance, will take their own route and may leave at different times. These patterns of migratory behaviour have evolved since the last ice age ended about 10,000 years ago. In evolutionary terms, this is little more than the blink of an eye, suggesting that the inherited part of migratory behaviour depends on a very small number of genes.

But there is more to these extraordinary journeys than a genetically determined street guide. In order to navigate thousands of miles to their winter habitats, our willow warblers rely on a variety of skills, some innate, some learned.

A willow warbler at Marakele National Park, Limpopo, South Africa.

During daylight hours, they augment their built-in ability to use the sun as a compass by tracking landmarks remembered from previous migrations: rivers, coastlines or mountain ranges. They can adjust for windspeed and direction and appear to use species-specific checkpoints, for course-correction. At night, particularly in the long continuous flight over the desert, they navigate by the stars and Earth’s magnetic field. There is evidence that their senses of smell and hearing also contribute.

Willow warblers travel slowly, taking between six and twelve weeks to complete the journey, stopping to feed at gathering places that have been used for generations before tackling arduous stages. Most birds stop at one or more such sites before undertaking the thirty hour flight over the Sahara Desert, and at least one afterwards in order to recover.

After the Sahara, things become easier and, working your way slowly southwards, you should be in southern Africa for Christmas. No other bird makes a longer or more dangerous migration to their winter feeding grounds. Bon voyage!

REFERENCES

RSPB: https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/bird-migration

Movement Ecology: https://movementecologyjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40462-018-0138-0

Oxford Academic – Behavioural Ecology: https://academic.oup.com/beheco/article/27/3/865/2365973

Nature Communications: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-35788-7

I like the references at the bottom of the post. Vey useful

There is a fine line between purveyor of interesting information and total nerd – and I hope I didn’t just cross it.

The willow warbler’s journey is amazing, they are such small birds you wonder just how they manage to do it!

I love all the information, not nerdy at all just really interesting.

Barbara Johnson

Thank you, Barbara.